For the week including November 12, 2010

THE LEONIDS ARE COMING

Bright shooting stars have been falling in the late evening reminding us that it’s time again for the best of the annual meteor showers to come our way. The Leonid Shower, so called because the meteors stream from the direction of the constellation of Leo, the Lion, will reach its peak on the morning of November 18th.

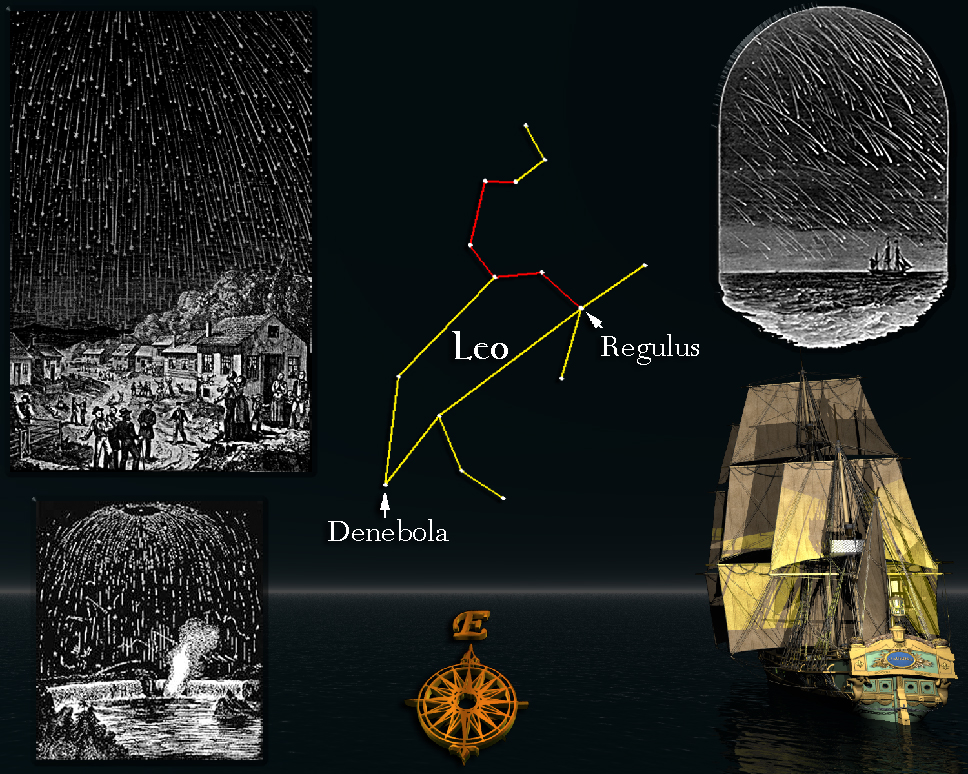

The Leonids have a special place in history because it was this shower that finally revealed to astronomers what the nature and origin of meteors were. For centuries it was believed that the occasional “falling star” seen in the sky was a phenomenon of the Earth’s atmosphere that was a sign of changing weather. Those who studied and tried to predict the weather came to be called meteorologists. In 1799, the Leonids exploded in a meteor storm that was reported around the world. The inset illustration at upper right gives an impression of the event. One witness, a sailor off the Florida coast, wrote, “About two o'clock in the morning, I was called up to see the shooting stars, (as it is vulgarly termed,) the phenomenon was grand and awful, the whole heavens appeared as if illuminated with skyrockets, flying in an infinity of directions, and I was in constant expectation of some of them falling on the vessel.” The meteor storm appeared again in 1833. The inset illustrations on the left depict what was seen that night when some 150,000 meteors an hour fell. Observers noted for the first time that the meteors seemed to come out of the constellation of Leo. While the 1799 shower was a great curiosity for the world, the 1833 storm was a focus for astronomers. They were able to determine that the meteors were coming from beyond the Earth’s atmosphere, but still hadn’t found what was creating them. That changed with the discovery of William Temple and Horace Tuttle’s comet in 1866. Their calculation of the comet’s 33-year orbit matched the appearance of the meteor storms. Astronomers theorized, and later confirmed, that the Earth’s yearly passage through the trail left behind by comet Tempel-Tuttle was the cause of the Leonid showers. When the comet tail’s minute debris fragments hit the Earth’s atmosphere they burn up in our skies as meteors.

Everyone began looking forward to a great meteor storm in 1899. But in 1899 and 1933 neither Comet Temple-Tuttle nor a meteor storm were seen and scientists began to wonder if some mistake had been made. In 1965, the long-lost comet was seen again and in 1966 the skies of Texas filled with meteors. During this tempest an estimated 240,000 meteors an hour fell. One witness described the meteors as being about half as numerous as snowflakes in a snowstorm.

The forward edge of the comet’s debris trail has been giving us some great shooting stars for the past few nights, but this year’s Leonid meteor shower peaks next Thursday morning.If you’d like to watch it build toward its climax, dress warmly and head out near midnight on Wednesday to a dark place where you have an unrestricted view to the east. A lawn chair, thermos of coffee, and a blanket aren’t bad ideas either. When you’re all set up, look to the east and you will see the head of Leo, the Lion, rising above the horizon. The meteors will stream from a broad area of the eastern sky, but if you trace their paths backward, they will seem to be streaming from the head of the Lion.

Unless otherwise indicated, all content of this web site is the copyright of Robert Deegan and all rights are reserved.

For more information, or to comment, please contact: Bob@NightSkies.org