For the week including April 23, 2010

THE GIRAFFE

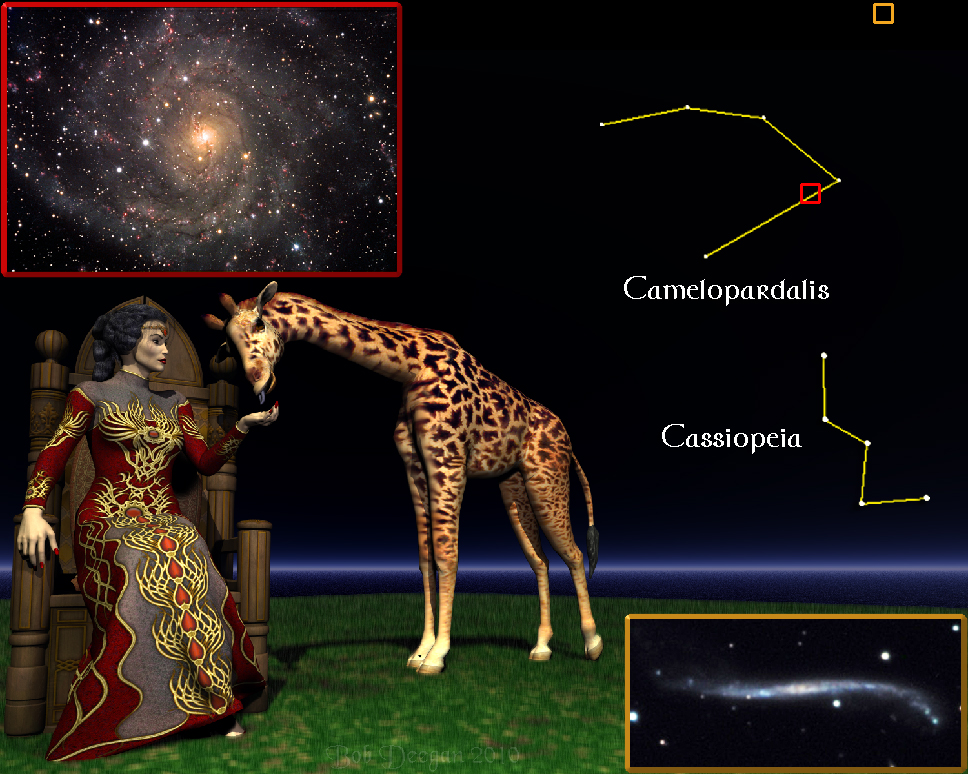

People sometimes ask me how the constellations came about and whether there any rules to follow by which you cans find their boundaries in the sky. The answer is that most of the constellations were handed down to us from ancient times and their boundaries have meandered quite a bit. In 1929, the International Astronomical Union established the modern list of eighty-eight constellations. They got rid of some constellations (Like Musca Borealis, the Northern Fly, which can still be seen in the stars painted on the roof of New York’s Grand Central Station.) and stretched the borders of the remaining ones to include stars that are only visible in telescopes. Today, because of these faint stars, there’s little telling with the naked eye exactly where one constellation ends and another begins. Some constellations seem to be composed entirely of stars that are too faint to see ordinarily. For instance, can you find the giraffes in the accompanying illustration? OK, one is fairly easy to catch, but the other is among the stars in the constellation of Camelopardalis, the Giraffe. This constellation is one of the more recent entries in astronomy’s celestial atlas. It was first plotted by Jacob Bartsch in 1624 and its name is derived from the ancient Greek meaning “leopard spotted camel”. The stars of Camelopardalis are very dim, so finding this giraffe in the sky isn’t too easy. When asked to point it out at night, most astronomers just say, “It’s over there near Cassiopeia.” This turns out to be a good description of its location. When you go looking for Camelopardalis, first look to the north and find the prominent “W” shape of stars belonging to Cassiopeia, the Queen. The Giraffe occupies the fairly empty space just above it.

Here are just a couple of the strange sights that can be found in this elusive constellation:

The Integral Sign Galaxy (lower right photo): Far too distant and faint for most telescopes available to amateur astronomers, this spiral galaxy is well known for its resemblance to the mathematical symbol. Our edge-on view of the galaxy reveals it as one of the thinnest yet discovered. A brushing pass by another galaxy set the integral galaxy in motion, disturbing its shape into its present form.IC 342 (upper left photo): A favorite of the fainter galaxies that can be captured with a good backyard telescope. IC 342 is a member of a group of galaxies that lies just outside the thirty galaxies of our Local Group. This galaxy group, which includes Maffei 1 and 2 as well as the recently discovered Dwingeloo 1 and 2 (Love those names!), has a curious history. Billions of years ago, the two largest member galaxies of our Local Group, the Great Andromeda Galaxy and our own Milky Way, were using their immense gravity to gobble up and absorb smaller galaxies in their path. As a result of the great gravitational tides that ensued, some of the galaxies destined for this cannibalistic feast were actually pushed out of harm's way and are now receding away into space. Because this group of galaxies lies close to the equatorial plane of our Milky Way, they are obscured by a great deal of gases and dust. But it's estimated that they have traveled some 10 million light years since their escape.

Integral Sign Galaxy photo credit: Bonnie Fisher and Mike Shade/Adam Block/NOAO/AURA/NSF

IC 342 photo credit: Ken and Emilie Siarkiewicz/Adam Block/NOAO/AURA/NSF

Unless otherwise indicated, all content of this web site is the copyright of Robert Deegan and all rights are reserved.

For more information, or to comment, please contact: Bob@NightSkies.org