For the week including April 2, 2010

A WATERY MARS

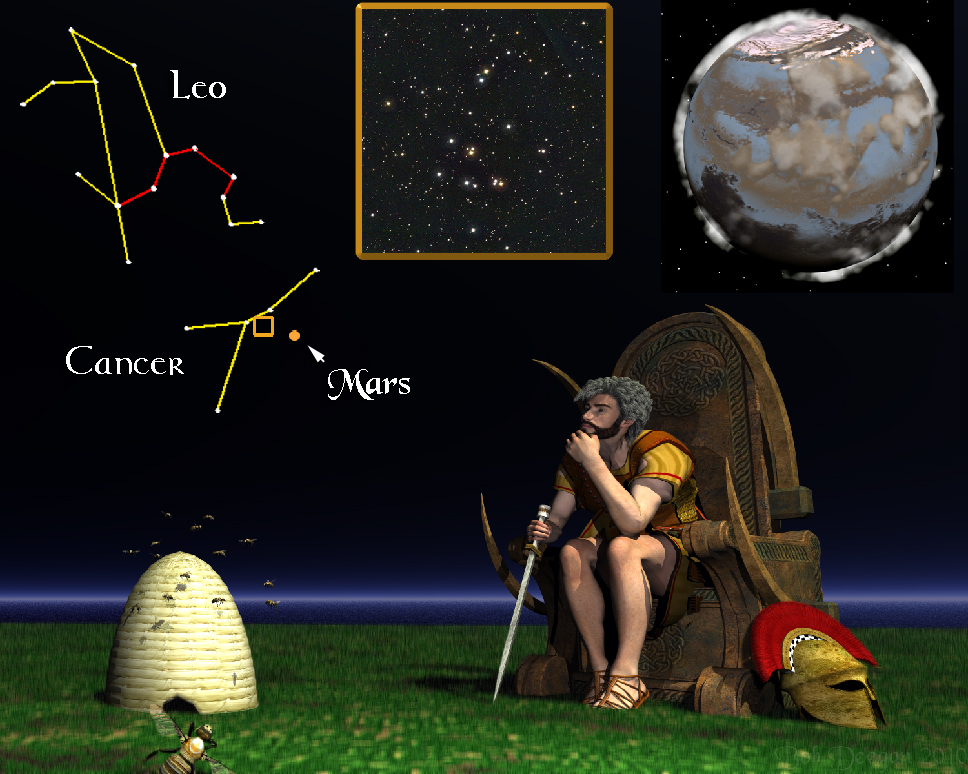

Folks have been asking about the reddish star in the west visible after midnight. For those who haven’t had a chance to look for it, this “star” is actually the planet Mars. You won’t have a difficult time finding it; Mars will be the brightest object in the western sky and can be seen below the prominent sickle-shaped stars in the constellation of Leo, the Lion. Mars, named for the Roman god of war, is now in the constellation of Cancer, the Crab, near the Beehive – a cluster of stars just discernible to the naked eye. Shown in the National Optical Astronomy Observatory photograph at upper center in our illustration, the Beehive cluster is a favorite of binocular star gazers and has been noted by astronomers since ancient times.

In 1666, Gian Cassini discovered that Mars had a polar ice cap and astronomers began to wonder if that planet might share other features of our fertile Earth. More similarities were found over the centuries and by the time American astronomer Percival Lowell completed his trilogy of books in 1908 “proving” the existence of an advanced civilization on the red planet, the thought that there might at least be some life on Mars didn’t seem so far-fetched.

Further research quelled much of the enthusiasm about possible Martians. The planet’s thin atmosphere is incapable of allowing water to flow across its surface in the liquid form that life requires. But orbital photographs have shown many regions with surface features that are nearly identical to water formed areas of the Earth and scientists now speculate that Mars may have had vast amounts of surface water in its past and that life may perhaps still exist deep beneath that surface.

The excitement about liquid water on Mars and the possibility of life having been, or still existing there, resurged six years ago when the roving explorer Opportunity bounced down in Meridiani Planum. Like Spirit, its robotic sibling, Opportunity was designed to sample the soil and rocks of Mars to see if the planet once had liquid water flowing on its surface. Scientists were delighted when Opportunity’s camera showed that it had landed right next to an exposed outcropping of layered rock that looked perfect for testing. The rover went right to work and in March of 2004 NASA released an epic finding when spokesperson, Dr. Ed Wyler, announced, “Opportunity has landed in an area of Mars where liquid water once drenched the surface. Moreover, this area would have been a good, habitable environment for some period of time.”

NASA’s evidence came in four main findings.

1. Spherical mineral nodes are scattered through Opportunity’s rock samples. Dubbed “blueberries”, the specimens were sliced open and viewed microscopically. The examinations showed that the blueberries had not formed as a byproduct of volcanic processes, or meteor impacts, but had concreted -- “grown” within the rock much like a pearl forms in an oyster.

2. The outcrop also contained regularly structured gaps and holes made by the growth and erosion or dissolving of crystals. These structures are the same as those found in once submerged rocks on Earth.

3. An examination of elements in the rock revealed large amounts of sulfur, much more than had been found on Mars before. Opportunity ground away the surface and found high quantities of sulfate salts, another prime indicator of a significant body of water having been present that evaporated long ago.

4. Opportunity found lots of the mineral jarosite in the rock. Years ago, Roger Burns of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, had predicted that since iron based hematite was strongly indicated in the rusty soil of Mars, and the Viking landers sent there in 1976 had found sulfur, then jarosite crystals, although rare on Earth, should be abundant on a once watery Mars. Jarosite results from a reaction of sulfuric acid, iron, and other trace elements only when immersed in water.

There are also strong indications of sedimentary rock formations which are being investigated. If life once existed on Mars, this kind of rock, produced in ancient lakes, seas and oceans, may contain well preserved fossils.

At upper right in our illustration is an image of a watery Mars as it may have looked when its shallow seas were evaporating. Since Mars is not as geologically active as Earth and land elevations are generally more gradual, there aren’t conspicuous continents on the planet’s face. Seasonal changes to the amount of melt water from the polar ice caps might have changed the appearance of the planet even more.

Unless otherwise indicated, all content of this web site is the copyright of Robert Deegan and all rights are reserved.

For more information, or to comment, please contact: Bob@NightSkies.org