For the week including January 22, 2010

CANCER, THE CRAB

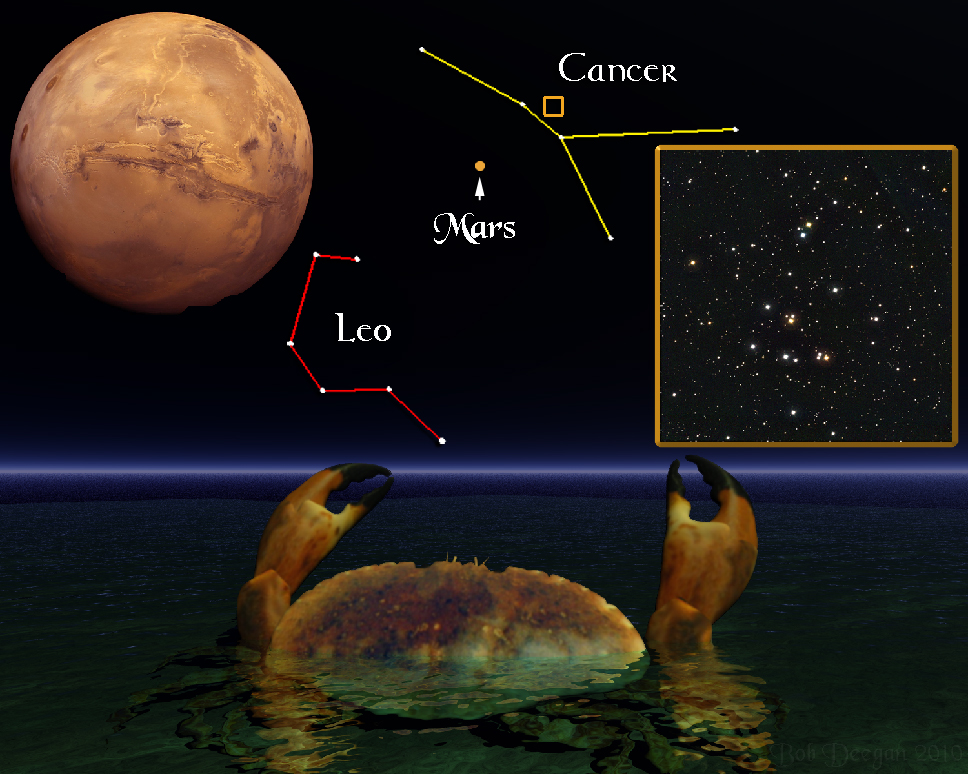

The constellation of Leo, the Lion is a group of stars that’s very easy to spot as it makes its evening rise in the east. Just nearby, there is another constellation that has been plotted on star maps for thousands of years. Apparently a crab-like shape was not high up in the list of criteria for the constellation of Cancer, the Crab, when it was first laid out. In fact most of its stars are so faint you may have to squint a bit to make them out. Cancer isn’t hard to find though. Right now, the red planet Mars stands below it making it easy to locate. To find Cancer, face east after 8pm and you’ll see a sickle-shaped collection of fairly bright stars near the horizon. These stars mark the mane and chest of Leo, the Lion. Above and to the right of this group, is the planet Mars which is fun to watch as it moves among the background stars during its orbit around the Sun. Currently, Mars is in retrograde, meaning that its normal motion among the stars has reversed direction. Generally, Mars moves in the direction of the eastern horizon, but last month it slowed to a stop in the constellation of Leo and since then it has been moving backward up the sky toward the constellation of Cancer. This March, Mars will again slow to a stop in the night sky and then resume its regular movement. It will be back among the stars of Leo, the Lion, in May. This forward, stop, go backward, stop, go forward again movement of Mars may seem strange, but it happens every year. It’s actually pretty easy to see why it happens when you take a look at the diagram shown here.

Back in the 1970s, the NASA Viking Orbiters took the mosaic photograph of the Martian surface shown at upper left in our illustration. The reason Mars looks so rusty-red has to do with the large amounts of rust (iron oxide) in the planet’s soil. Mars has a very thin atmosphere, about a hundred times thinner than Earth’s, so with few clouds to block the view, we get a pretty good look at the color of the Martian surface. Mars has a wide collection of geologic wonders and is home to the solar system’s largest volcanoes. One of them, Olympus Mons, covers an area the size of Arizona and has an elevation three times higher than Mount Everest. Another outstanding feature visible in the photograph is the vast canyon system of Valles Marineris, the largest and deepest ever seen in nature. Imagine a miles-deep canyon long enough to cut across the United States and create a huge channel that connected the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. That’s almost what Valles Marineris is like. It extends 2,500 miles, spanning a fifth of Mars’ surface, and plunges to a depth of six miles. Scientists are still puzzling over the origins of these Martian landmarks. A promising new theory explains them as the result of collisions with huge meteors and future NASA missions to the planet may turn up the evidence to prove it.

While you’re looking at Mars, you may notice a hazy patch of light near the center of Cancer, the Crab. At a distance of 577 light years, these are stars that are too far away to be resolved with unaided vision, but their glow, which covers an area larger than the full Moon, is easy to make out. More than two thousand years ago, the Greek poet Aratus referred to them as the “little mist” and said that an inability to see their shine on a clear night foretold of stormy weather. Shown in the National Optical Astronomy Observatory photograph at right in our illustration, these stars are called the Beehive today. The hundreds of stars inside the Beehive condensed from of a great cloud of hydrogen almost half a million years ago.

The Beehive belongs to an astronomical class of objects called an open cluster. Open clusters are a collection of stars that have a common origin and group together because of shared gravitational attraction. Through a telescope, it’s fairly easy to identify these clusters – they generally look like a large “clump” of stars gathered together in space. Because they’re so many light years away from us, it’s hard to see that there is a tremendous distance between the individual stars of the cluster. If we were much closer to them, the gap between the stars could become so great that we might not recognize a cluster at all. The open cluster of stars we call the Big Dipper is a good example.

Unless otherwise indicated, all content of this web site is the copyright of Robert Deegan and all rights are reserved.

For more information, or to comment, please contact: Bob@NightSkies.org